My painterly pedigree is distinctly anti-modern. I trained, by apprenticeship to Ernst Fuchs, in a glazed tempera technique. When I saw Doig’s paintings for the first time, it was like Alice finding that little door in the wall. Except, instead of stumbling into a fairy world I squeaked through the crack under a door so big I could barely comprehend it’s existence, into the opulent and dizzying palace of High art.

Funny that because Doig probably wouldn’t think of himself in terms of art with a capital A. But he seems to have stumbled into it. Matthew Collings wrote:

“Peter Doig’s achievement is to give the audience what it thinks it wants, while remaining connected to some kind of genuine painting culture.”

There was a quality I had been searching for in my own work, gesturing towards something like rapture. Based on reality but removed from it just enough to elicit something like intellectual ecstasy. The Akron/Family band sings:

“I have to sing something if I want to sing, but it’s not about the words it’s about my voice rising to a place my fingers can’t reach and my legs are so tired from all this standing still”

The idea of reaching for something, trying for it it different ways, ascending by some earthly means. This was a quality I was seeking in my work, I found it in old icons. But other people didn’t, not necessarily. And in Caspar David Friedrich; that sense of the sacred but not so wrapped up in stiff allegories. I wanted a new symbolism that expressed some part of that marginal space that looks out from mass culture to a place very far away, but leaves breadcrumbs for other people to find the way, remaining connected in some way, not pure fantasy.

Peter Doig. Blotter.

Then I saw Doig’s “Blotter” And I experienced that rapture, I found it in something new. A painting that doesn’t deny it’s a painting, but figurative and about some kind of internal discovery. Romanticism has not died, it changes forms, and it always will. It’s just no longer wrapped up in company policy about humanity being dwarfed by nature, or the forest as temple. Burtynsky, for example, is a kind of reverse romantic. “Look at what we’ve done” and it’s meant to elicit the same kind of feeling as Cole painting the Grand Canyon, saying “look at what we can’t do!” But I’m probably the first person to ever call Burtynsky a romantic.

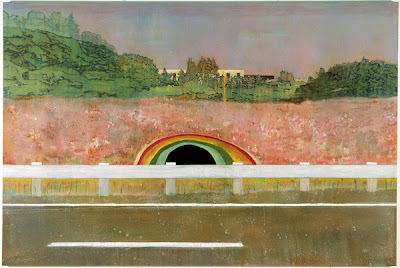

Peter Doig. Country Rock.

And then I saw Doig’s Country Rock. A marginal landscape; an underpass viewed from the window of a passing car. But it’s all pink and green and beautiful. Just abstract washes and that insistent rhythm of the guard rail, and the outline of those trees laid on top with a projector. Perfect. You wouldn’t expect beauty from a highway scene, but you can find it if you look, like Burtysnky found it in industry. Maybe we shouldn’t find it, but we can. That’s what I find so interesting.

Edward Burtynsky. Manufactured Landscapes: C.N. Railcuts No. 1

What does Doig say about being a romantic:

“Yes I probably am a romantic, and I guess therefore that it follows that the paintings are probably romantic too. I think in a way to be making paintings and, to invest as much time as I have in the activity of painting, then you have to be a romantic really, particularly with the kind of paintings that I make, with the subjects that they depict.”

The third painting I saw by Doig was the painting “Ski Jacket.”

Peter Doig. Ski jacket.

Ski Jacket was based on a photograph.

So “genuine painting culture” it is. Doig joins the company of other contemporary artists like Gerhard Richter, who bring the practice of painting up against newer kinds of visual technologies (photography, cinema, computer screens etc.) Johanne Sloan mentions this connection in her essay Hallucinating Landscape and she also says: “…There is a shared acknowledgement [among contemporary painters - here the YBAs] that painting has value at the present time as a way of negotiating a dense visual culture.” A way, I take it, to find beauty or significance in a sea of images by investing time in one.

Caspar David-Friedrich. Monk By The Sea.

No comments:

Post a Comment